|

Harold Lancour and West African Librarianship

Basil Amaeshi

|

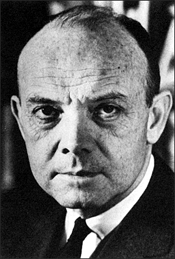

Portrait of Harold Lancour.

Courtesy of Prof. William Nasri. School of Library and Information Science, University

of Pittsburgh. |

Harold Lancour's monumental report on "Libraries in British West Africa" [1]

has had far-reaching consequences. Much has changed in the region in the subsequent thirty years: the

colonies he visited have become independent, and their populations have grown enormously. For example

Nigeria has grown from 34 million to over 100 million persons. Considerable economic growth has also come

to pass, and the library movement has made significant advances. However, some of the problems identified

by Lancour still exist. Despite good supplies of natural resources, prosperity has not reached West Africa;

societal polarizations remain intractable; various degrees of political turmoil are found throughout the

region, with the possible exception of Gambia.

West Africans, Lancour observed, shared with Americans a high value placed upon education. But in terms

of libraries, if the 1950's African was fascinated by them, the 1990 counterpart would appear to be largely

indifferent to them. And the fascination with European/American culture, which he found to be typical

among Africans of the 1950's, is rare today. Yet, all things considered, the tale of West African librarianship

since 1958 is largely a success story. Lancour could hardly have imagined that by 1982 there would be

24 university libraries in Nigeria, 29 polytechnic libraries, 28 college of education libraries, 19 public

library systems, and 61 special libraries. Holdings are in some cases substantial: public libraries range

from 57,000 to 500,000 volumes; universities range from 25,000 to 700,000 volumes. A directory of libraries

in Ghana, published in 1974, comprised 62 pages; it included seven public library systems, 12 academic

libraries, and 32 special libraries. In the Gambia there is a national library and an academic library;

in Sierra Leone there are three public libraries, 11 academic libraries and 18 special libraries. But

it is in library education-the focus of the Lancour report-that progress has been most remarkable.

In the belief that the advancement of libraries depends upon professional leadership, Lancour recommended

the creation of a postgraduate program in librarianship. He pointed to the University College at Ibadan

as a suitable home for that program. And in 1960 that College (now a University) began a training course

to prepare candidates for the (British) Library Association registration examinations. This evolved into

the Institute of Librarianship in 1963, offering an independent diploma. Not without considerable opposition

within Nigeria, this curriculum became a post-graduate Master's program offered by the Department of Library,

Information and Archival Studies. Graduates of Ibadan have played decisive roles in the Nigerian library

movement. The requirement of advanced university education for librarians is no longer in dispute.

With that said, it must also be acknowledged that in the face of recent economic hardships library growth

has halted, and indeed there is difficulty in sustaining existing libraries in the region. Economic policies,

set up in response to the foreign debt problem, have devastated currencies, impoverished most of the educated

middle class, and reduced the ordinary populace to a level of near destitution. For many elements of the

population, survival needs rank first. In the libraries, there has been a struggle to pay staff in the

past few years, and book funds have virtually disappeared.

It may be that the mission of public libraries in such circumstances needs to be reconsidered. I have examined

elsewhere [2] the need for African libraries to articulate their purposes, and other

writers have written of the need for library service to address the needs of large rural and non-literate

segments of African societies. However, it should not be supposed that Africa should ignore the technological

advances available to libraries in order to throw all resources into service to the rural population.

Africa needs information technology for development; library automation should facilitate access to knowledge

that may bring national economies out of their backward, primary-producer stage into healthy modern forms.

Both rural and urban populations have a stake in the success of that transformation. The underlying theme

of the Lancour report, that librarians should have the most advanced education so that their libraries

can keep pace with those in any part of the world, is to be cherished now, in times of recession, as much

as it was in periods of growth.

References

1. Harold Lancour, "Libraries in British West Africa: A Report of A Survey for the

Carnegie Corporation of New York, October-November 1957," Occasional Papers No. 53, University

of Illinois Library School, 1958.

2. Basil Amaeshi, "Public Library Purpose in Underdeveloped Countries: The Case of

Nigeria," Lihri 35-1 (1985): 62-69.

About the Author

Basil Amaeshi is Director of Library Studies, Imo State University, Okigew, Nigeria. He holds degrees

from the University of Ibadan and the University of Ife, and is an Associate of the Library Association

(UK). His publications have appeared in International Library Review, Libri, and Nigerian

Libraries. During 1989-90 he was at Rosary College, as a Visiting Scholar in the Graduate School of

Library and Information Science; he also served as Assistant Editor of TWL. In summer 1990 he was

a Visiting Scholar at Rutgers University.

© 1990 Basil Amaeshi

Top of Page | Table of Contents

|